Vibe Coding Isn't About Vibes

It's rhetoric & knowledge

This semester I’ve been frustrated by the inadequacy of institutional tools for doing the kind of writing I want to do in the classroom.

The biggest problem? Tracking student work without grading.

I don’t give grades in my writing courses because they only get in the way of learning to write. When students face a grade, they stop experimenting.

They play it safe and avoid the kind of risk-taking that actually develops writing ability. Experimentation is key to becoming a good writer, and students are less likely to experiment with a grade on the line.

This year I’m taking a “writing gym” approach with my essay course. The concept is simple: treat writing like strength training. You build writing ability through consistent daily practice, not occasional high-stakes performances.

Students:

track daily word counts

work in three-person accountability pods, and

focus on showing up rather than producing perfect drafts.

Complete or not complete? Did you do your practice or not?

But learning management systems are built for grades. They’re designed around point systems, percentage calculations, and assignment submissions. They make tracking daily practice without numerical judgment nearly impossible.

So at the start of the semester, we used a tool called 750 Words, which was perfect for this approach.

This tool encourages writers to write 750 words every day with a simple interface that tracks and rewards regular writing. It’s a great tool … You should check it out.

Then halfway through the term, I discovered they no longer offer a free version. I can’t make students pay for a required tool after the semester has started, and I certainly can’t afford to pay for 25 students myself.

So I thought: Why not build my own tool?

As most of you know, I’ve been experimenting with using instructional chatbots in the classroom. More recently, I’ve been using Claude to develop apps on top of my structured knowledge that can helps students in more focused ways than a chatbot can.

This seemed like the perfect opportunity to go deeper.

I’m currently revising my PromptOps course into something more foundational called Writing with Machines, exploring how structured content and knowledge architecture make AI collaboration actually work.

Building this tracker would let me test those principles in practice.

But what are “vibes” actually? From a rhetorical perspective, vibes represent an intuitive sense of what works—a feel for audience, context, and appropriate response that skilled practitioners develop through experience.

Last year I played around with vibe coding tools like Replit and Lovable, but found them fairly limited. They cap the number of interactions you can have daily, and deployment remained complicated for someone without deep technical background.

After spending three months developing the writing gym pedagogy through conversations with Claude, I realized that the accumulated knowledge turned out to be more valuable than any deployment feature a specialized platform could offer.

The Strategic Choice

Andrej Karpathy, OpenAI co-founder, coined the term “vibe coding” to describe developers who “fully give in to the vibes” and “forget that the code even exists”—focusing on iterative testing and prompt refinement rather than examining actual implementation.

But what are “vibes” actually? From a rhetorical perspective, vibes represent an intuitive sense of what works—a feel for audience, context, and appropriate response that skilled practitioners develop through experience.

The ancient Greeks called this metis … or cunning intelligence, the ability to navigate complex situations through accumulated practical wisdom rather than formal rules.

I’ve written before about metis in the context of accessibility and neurodivergent use of AI. Many people have developed sophisticated intuitive strategies for working with AI systems that appear casual but reflect deep understanding of communication patterns.

But its important to realize that any kind of vibes or cunning intelligence rely on practical wisdom, which emerges from expert knowledge. So you can support your vibes (or your metis) by grounding those vibes in structured thinking about your domain.

The “vibes” in vibe coding work the same way. They’re not mysterious or magical. They’re accumulated rhetorical knowledge about what prompts work, what contexts matter, how to frame problems effectively.

But it’s important to realize that any kind of vibes or cunning intelligence rely on practical wisdom, which emerges from expert knowledge. So you can support your vibes (or your metis) by grounding those vibes in structured thinking about your domain.

I didn’t stumble into Claude for this project. I chose it deliberately because that’s where my knowledge lives. My best vibes work on top of knowledge I’ve thoughtfully curated.

For three months before attempting to build anything, I’d been developing my “writing gym” pedagogy through conversations with Claude:

Working out how students track progress,

Testing why pod-based collaboration creates accountability,

Refining what “complete/incomplete” assessment means for student motivation, and

Exploring how fitness metaphors reframe writing as daily practice rather than occasional performance.

Each conversation added to a growing knowledge base that Claude could access and build upon.

When I finally said “help me design an app for this,” Claude was able to generate interfaces that reflected my pedagogical philosophy without much work.

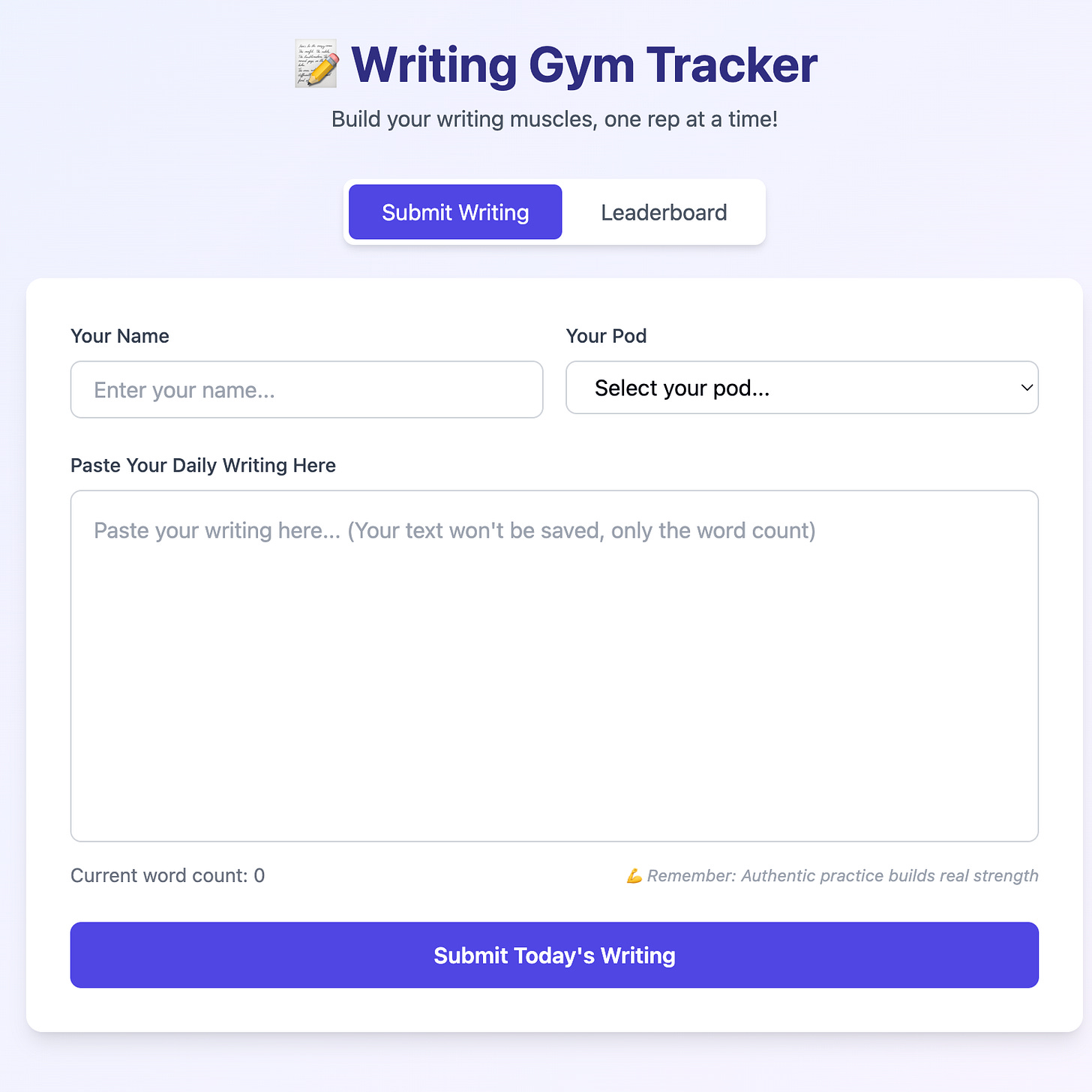

In the main submission interface, the tagline alone—”Build your writing muscles, one rep at a time!”—captures the entire pedagogy without me ever explicitly saying “use fitness metaphors throughout.”

Also notice the reminder at the bottom: “Remember: Authentic practice builds real strength.” I never wrote that copy. Claude generated it based on our conversations about how consistency matters more than perfection and how authentic practice builds capability.

The interface doesn’t save the actual writing, only the word count. This wasn’t a technical limitation, but a pedagogical choice that emerged from our discussions about removing evaluation anxiety. Students can practice freely knowing the text disappears, but their commitment to showing up gets tracked.

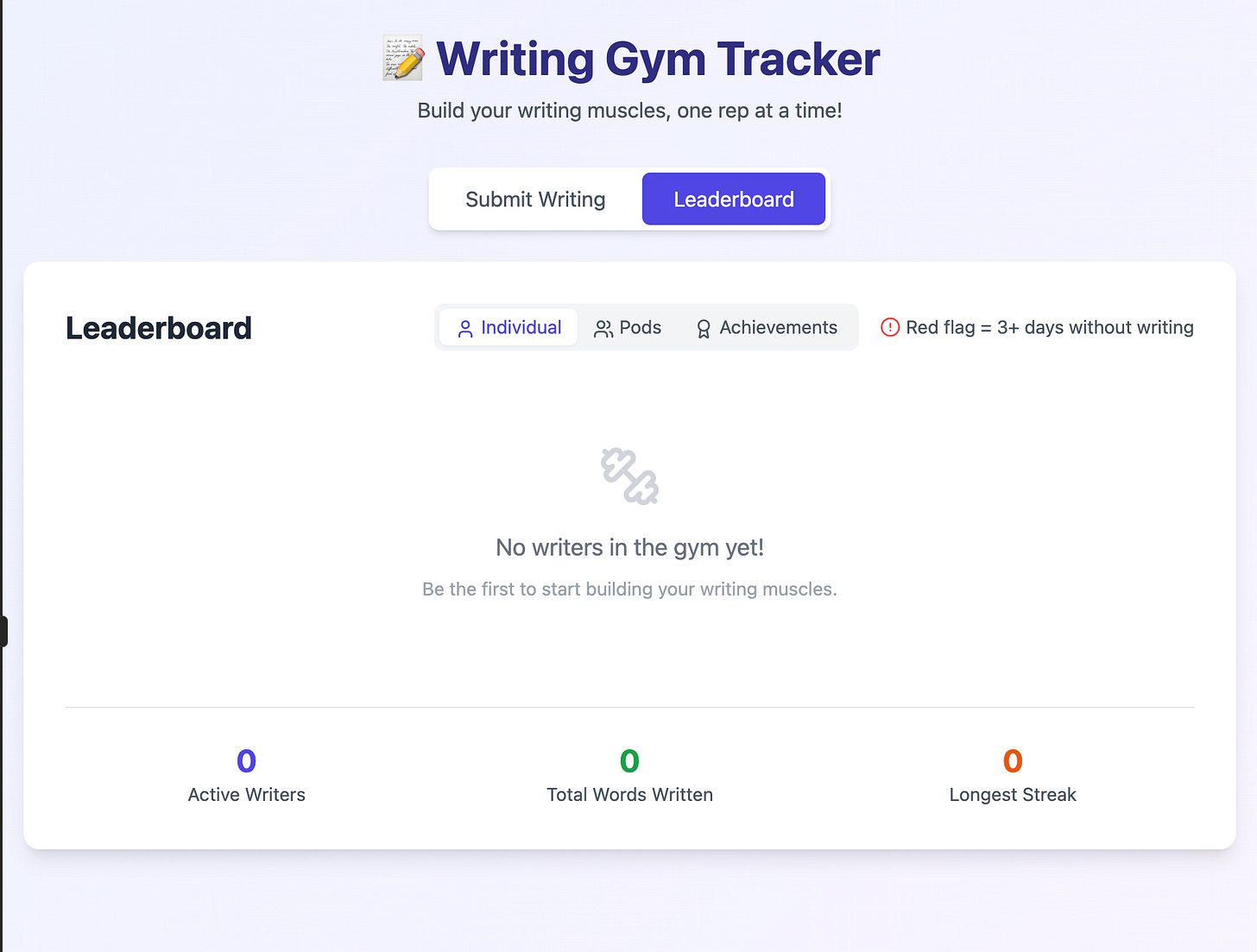

The leaderboard structure reflects our conversations about different types of motivation:

individual tracking

pod-based collaboration, and

achievement systems.

Notice the red flag indicator: “3+ days without writing.” Not punitive, not grade-based, just a visible accountability signal that emerged from discussions about how to maintain consistency without shame.

The empty state copy continues the fitness metaphor throughout the entire experience: “No writers in the gym yet! Be the first to start building your writing muscles."

This wasn’t me writing every piece of microcopy. This was Claude understanding the tonal consistency required by the pedagogical framework.

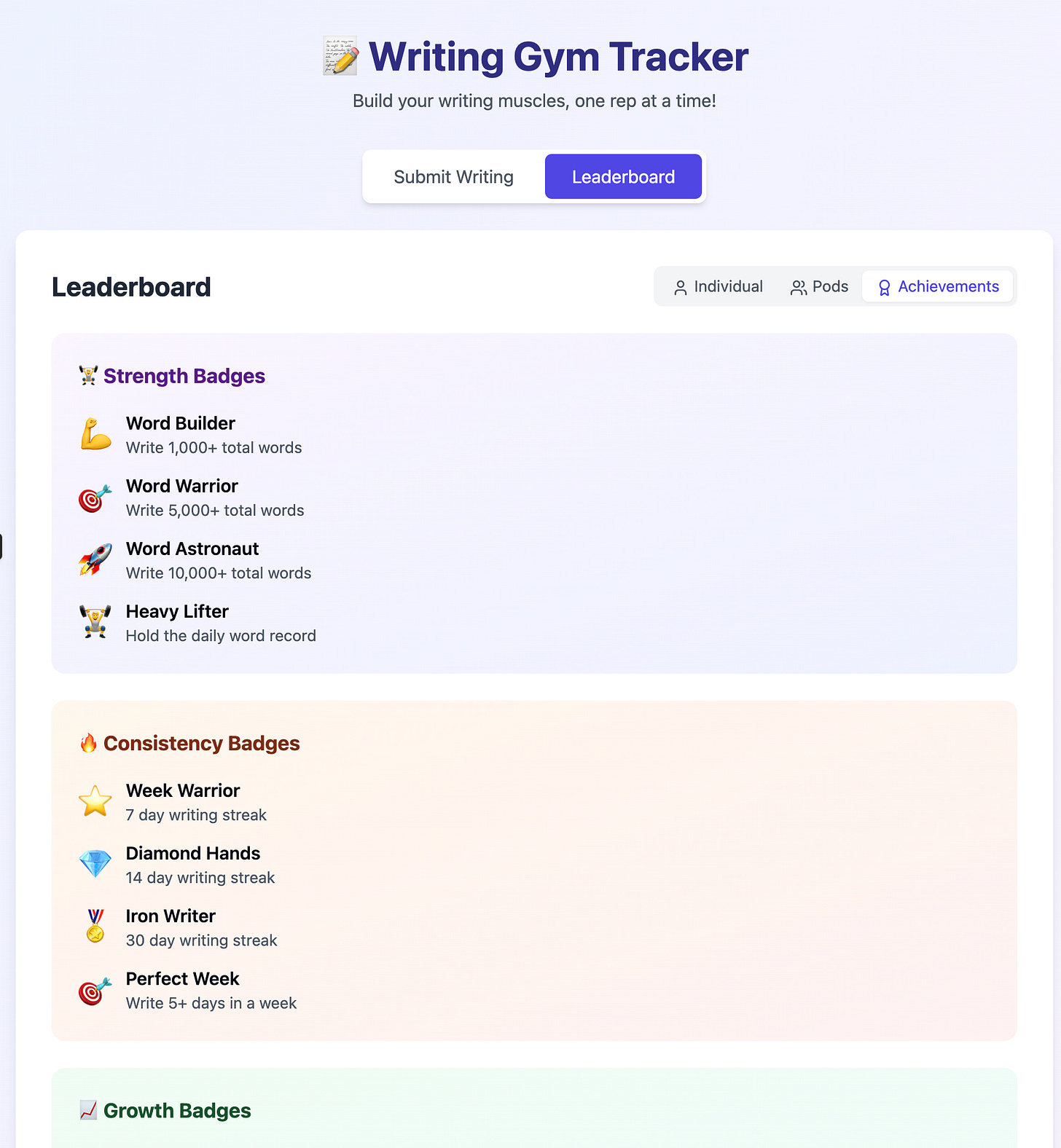

The badge system demonstrates how Claude structured the gamification badges around the core principles we developed.

Strength Badges (💪) focus on cumulative output: Word Builder, Word Warrior, Word Astronaut, Heavy Lifter.

But notice they’re not competitive in a harmful way—they recognize volume while the “Heavy Lifter” badge celebrates daily record holders.

Consistency Badges (🔥) prioritize what matters most in the writing gym: showing up. Week Warrior, Diamond Hands, Iron Writer, Perfect Week.

Now, honestly, I do think these metaphors could use some work. For example, I’m not so sure about warrior metaphors or diamond hands … But that’s easy to change.

These names didn’t come from me listing badge options, but rather from Claude understanding that consistency matters more than perfection in building writing capability.

The categorization itself (Strength, Consistency, Growth) maps directly to our pedagogical conversations about what writers actually need to develop. I never handed Claude a badge taxonomy. The structure emerged from accumulated knowledge about how writing skill develops.

This is what working with pre-structured knowledge looks like. Not prompting from scratch, but building from a foundation of organized thinking.

The Bridge to Implementation

After developing the app concept in Claude, I faced reality: Claude can’t deploy backends. Any app that needs to work for multiple users on multiple devices requires a database, authentication, and other security measures.

I needed to move to a platform with deployment capabilities. But I didn’t have to start from scratch.

I learned something new in this process. Paying for the platform where you build and structure knowledge can save significant money when you deploy to constrained platforms. The upfront investment in organization returns dividends when you transfer that knowledge efficiently.

I had Claude generate a comprehensive prompt for Lovable that captured our entire design process, using my structured prompt principles.

Below are a few excerpts. Paid subscribers can find the full prompt here.

[CONTEXT] I’m building an educational web application to help students

develop consistent writing habits in a classroom setting. The concept

treats writing practice like fitness training—students track their

“gains” and compete on a leaderboard to stay motivated. Teachers need

a simple way to monitor participation and total output without reading

every submission.

...

[GUIDELINES]

Design and Visual Theme: Create a modern fitness-inspired interface

that feels motivating rather than academic. Use a purple gradient

background flowing from #667eea to #764ba2.

Messaging: Use fitness-themed encouragement throughout, such as “Build

your writing muscles, one rep at a time!” Provide positive feedback

after submissions. Keep the interface clean and distraction-free so

students focus on writing rather than navigating complex menus.

...

[CONSTRAINTS]

* Store student information including names, pods, word counts, and

submission timestamps in the database

* The leaderboard must update in real-time when any student submits

new writing

* When they submit, save only the word count to the database (not the

actual text content)

The decision to save word counts but not actual text isn’t because we can’t build that kind of app. It was a pedagogical choice that emerged from our conversations about removing evaluation anxiety.

The fitness-themed encouragement is a result of the metaphorical framework for reframing writing practice embedded in the prompt.

The real-time leaderboard updates reflect discussions about visibility and motivation in collaborative learning environments.

This prompt became the bridge between platforms. It packaged several months of structured thinking into a transferable format. Lovable could deploy what Claude had conceptualized because the knowledge was already organized, structured, and ready to transfer.

The prompt was a pedagogical philosophy translated into implementation requirements through expert knowledge and practical wisdom. Every design decision, every constraint, every interface element traced back to structured knowledge about how students learn to write.

Here’s the economic reality that makes this approach practical: developing that comprehensive prompt in Claude (where I pay for a subscription) allowed me to create a working app within Lovable’s free interaction limits.

Instead of burning through dozens of back-and-forth iterations trying to explain my vision from scratch, I had a single, well-structured prompt that captured everything.

The investment in building structured knowledge in Claude paid for itself immediately. Without that foundation, I would have exceeded Lovable’s free tier trying to communicate context, clarify requirements, and refine the design through iterative prompting.

I learned something new in this process. Paying for the platform where you build and structure knowledge can save significant money when you deploy to constrained platforms.

The upfront investment in organization returns dividends when you transfer that knowledge efficiently.

The Implementation Reality

Let me be honest about what happened next. The backend challenges were real and humbling.

Lovable gave me deployment capabilities, but I still needed to understand database structure, authentication logic, and security policies.

My app has real limitations:

security gaps I’m still closing,

password reset mechanisms, and

database authentication.

For my use case, these limitations are acceptable. We are just sharing word counts and friendly competition … Nothing high-stakes. This probably wouldn’t work for a lot of educational use cases.

But it go me thinking about things “vibe-coders” don’t tell you and why this asymmetry between frontend and backend exists?

Frontend development offers visual, immediate feedback. You see results instantly in browsers, making debugging intuitive. Visual errors are obvious. The declarative nature of HTML/CSS and component-based architectures map well to AI training patterns.

This is great for prototyping ideas fast. That shouldn’t be discounted, because it is an important part of software development. But if you want to deploy that prototype, it takes a backend.

Backend errors can corrupt databases, expose sensitive data, or cause catastrophic production failures. Database management requires optimization techniques that AI struggles to implement contextually. Deployment, infrastructure, real-time synchronization, security, and compliance all require architectural thinking that pattern-matching approaches fundamentally struggle with.

So it takes considerably longer to turn that prototype into a functional app.

That said, my app serves its purpose within real constraints. It’s functional enough for students to track daily writing, participate in pods, and build consistency habits while I continue learning what “good enough” actually requires in the world of vibe coding.

Start with Knowledge

So here is my key takeaway for anyone looking to give vibe-coding a try.

Start where your knowledge already lives.

The months I spent structuring my pedagogical thinking in Claude created a foundation that made everything else possible. When I finally needed to build, the knowledge was ready to go.

The “vibe” in vibe coding isn’t casual or magical. It’s accumulated expertise that’s been deliberately structured through systematic thinking and conversation. It’s the knowledge architecture you build before you ever start prompting for code.

This validates something I’ve been exploring in my research on AI content systems: pre-structuring knowledge beats post-processing it.

Whether you’re preparing content for RAG retrieval systems (which I’ve been writing about lately), designing for accessibility (which I explored at the CAKE Conference), or building applications through AI collaboration, the pattern holds.

The strategic organization of information upfront determines how well AI systems can work with it later.

You can’t fix bad structure with better algorithms.

You can’t compensate for unorganized knowledge with clever prompts.

The fitness metaphors, pod structures, assessment philosophy, and motivation principles in my app weren’t generated through prompt engineering—they emerged from months of structured conversation that Claude could access, understand, and transfer.

The “vibe” in vibe coding isn’t casual or magical. It’s accumulated expertise that’s been deliberately structured through systematic thinking and conversation.

It’s the knowledge architecture you build before you ever start prompting for code.

This is metis in action—practical wisdom that appears intuitive but is actually the result of careful organization and accumulated understanding.

My app worked not because I had perfect prompts, but because I had structured knowledge that let me evaluate what Claude generated, understand why certain design decisions mattered, and transfer that understanding across platforms.

I’ve been telling students for years that good writing requires genuine thinking, not just assembling words.

Turns out AI development works exactly the same way. The quality of what you build depends entirely on the knowledge you bring to the conversation … and more importantly, on how you’ve structured that knowledge for retrieval and recombination.

Where Are You Building Your Knowledge?

The future of AI collaboration isn’t in finding the perfect platform or crafting the perfect prompt. It’s in doing your thinking in places where that knowledge can accumulate, be structured, and transfer when needed.

Where are you doing your knowledge work?

Is it accumulating somewhere that AI can access and understand?

Are you structuring it through conversation, documentation, or systematic organization?

That choice might matter more than any tool decision you make.

Because when you finally need to build something, you’ll discover that the knowledge architecture you’ve been creating all along determines what’s possible.

The vibe in vibe coding? It’s not casual intuition or lucky guessing.

It’s metis—the cunning intelligence that comes from curating your domain expertise so thoroughly that working with AI feels intuitive.

It’s rhetorical knowledge that got there first.

What’s your experience been with building knowledge bases for AI collaboration? Where does your expertise live, and can AI systems access it effectively?

Reply and let me know what you’re discovering.