Content Modeling My 2025 and Beyond

What building a knowledge graph is teaching me about my own work

I spent the last week of December doing something I hadn’t planned: modeling my own Substack archive as a knowledge graph.

I’ve been writing about AI-ready content, structured knowledge, and retrieval systems for two years now, and I’ve been wanting to see if I could structure my posts in a way that would make them more useful … to me, to readers, and eventually to AI systems that might help people navigate the archive.

What I didn’t expect was how much the modeling itself became a form of reflection.

So as my first post of 2026, I thought I’d give you some of my reflections on where I’m going with this Substack and how this knowledge graph exercise is helping me in the process.

The Year of Narrowing

First, some context. 2025 was a year of cutting away.

When I started writing about AI in education and technical communication, fewer people were doing it. That’s no longer true. Everyone writes about AI and plagiarism now. Everyone has opinions about classroom policy. The general conversation doesn’t need another voice.

And, well, if I’m honest, my ADHD brain kind of finds those discussions a bit boring these days.

So I began focusing on other things in information design by narrowing in on questions where my background in rhetoric and professional writing gives me something distinctive to say:

How does retrieval-augmented generation work from a compositionist’s perspective?

What can classical rhetorical frameworks tell us about prompt design?

How do we test content systems, not just prompts?

Posts like “Is Structured Prompting Dead?” and “Testing as Rhetorical Proof” came from this narrowing.

So did the Deep Reading podcast episodes on topoi and AI hallucination.

I wrote less often but went deeper when I did.

This focus also shaped my teaching and research. I’ve got a couple academic articles in the works, and I’m starting this semester with an interdisciplinary grant project, where students and faculty from English, Sociology, and Computer Engineering are building a knowledge graph for a crisis food communication tool.

The structured content work I’ve been exploring publicly is now something I’m building with students, in real time, with actual users (and trying to bring into scholarly conversations).

My goal as an online writer has always been to bridge the space between the workplace and academia. In the world of AI, this is more important than ever.

What the Model Revealed

Back to the knowledge graph experiment.

I used Claude along with Neo4j’s data modeling MCP server, which is essentially a tool that helps you design graph structures.

For those unfamiliar: a knowledge graph represents information as nodes (things) connected by relationships (how those things relate). Instead of storing content as documents, you store it as a web of connected entities.

I started by asking: What are the meaningful units in my archive? Posts, obviously. But what else?

The first interesting decision was distinguishing Concepts from Rhetorical Frameworks. Concepts are the ideas I write about, for example structured prompting, RAG, AI literacy, vibe coding. Rhetorical Frameworks are the lenses I use to interpret those ideas—kairos, topoi, stasis theory, rhetorical proof.

I could have lumped these together. They’re all “topics” in some sense. But separating them forced me to articulate how the classical rhetoric is the interpretive layer through which I read everything else.

Kairos informs how I think about vibe coding.

Topoi shapes my understanding of RAG.

Memory connects to knowledge graphs.

Mapping these relationships made explicit what had been implicit across dozens of posts.

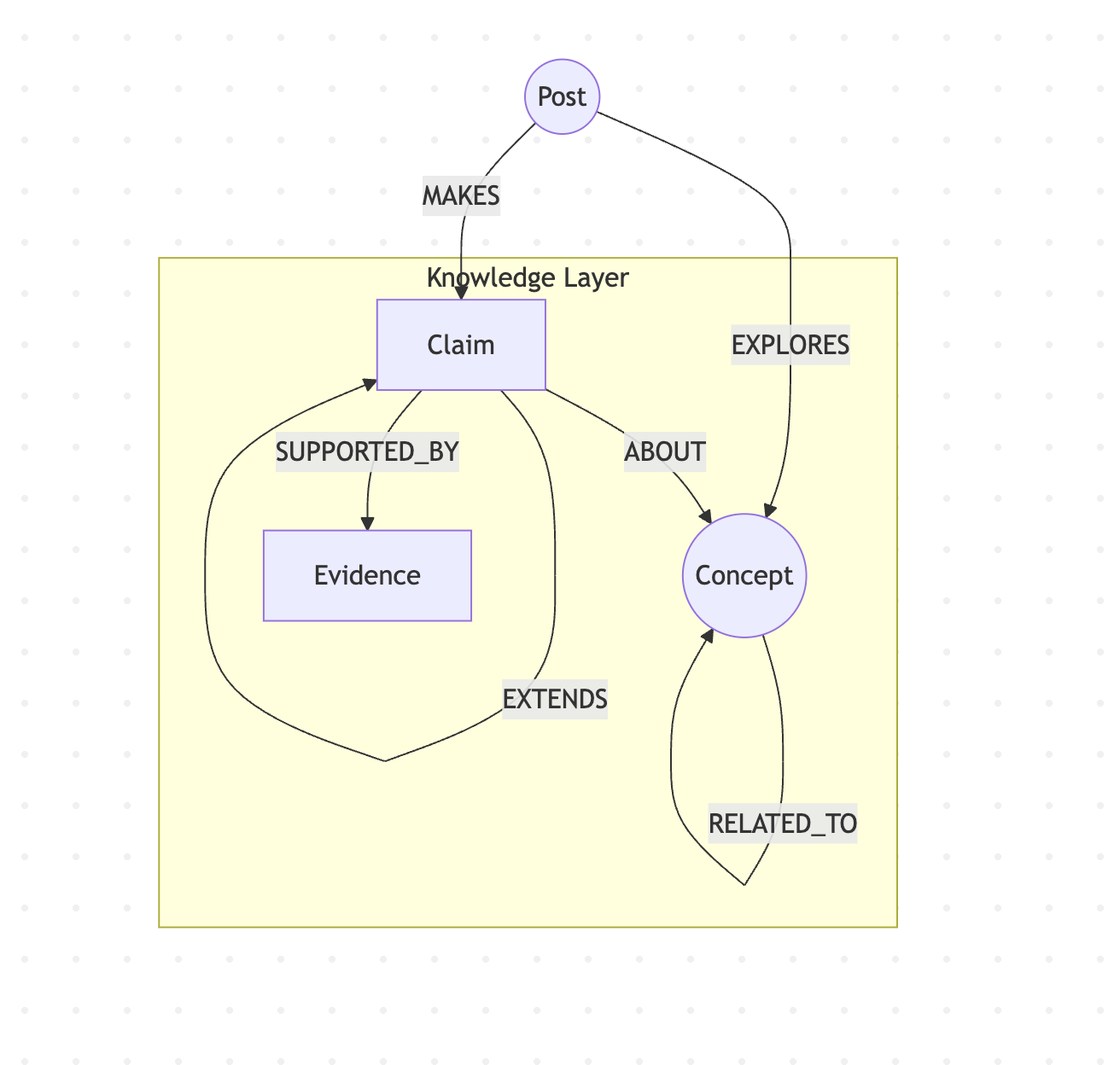

The second decision was adding Claims. Most writers think of posts as being “about” topics. But when I added a node type for Claims—with properties like statement, claim type, and confidence level, each post became a collection of assertions at various stages of development. Some claims I state definitively. Others I mark as provisional. A few are speculative, ideas I’m testing rather than defending.

Here’s the knowledge layer of the model:

This helps me understand that my archive isn’t just a collection of articles about topics. It’s a slowly developing argument, with claims that build on earlier claims, supported (or not yet supported) by evidence, attached to concepts that relate to each other in particular ways.

The EXTENDS relationship between claims might be the most useful part. My December post on rhetorical proof extends the prompt testing work from November.

Seeing that connection mapped changes how I understand what I’ve been doing. Not as isolated posts, but intellectual development over time.

When we create knowledge graphs for retrieval-augmented generation (and when we decide how to chunk content, what entities to extract, how to represent relationships) we’re doing philosophy whether we recognize it or not.

The Ontology Encodes the Epistemology

The usefulness of this activity goes beyond my own navel-gazing.

Knowledge graphs will become a key component to understand what we know (and what machines know) as AI becomes more ubiquitous.

Every knowledge graph encodes assumptions.

What becomes a node?

What becomes a relationship?

What properties matter?

These aren’t neutral technical decisions. They’re interpretive choices about what counts, what connects, what gets left out.

The model I built privileges argumentation—claims require evidence, ideas have lineages. It privileges rhetorical tradition as a distinct layer of interpretation.

Someone else modeling the same archive might structure it entirely differently. A computer scientist might emphasize technical concepts and tool relationships. A historian might organize by period and influence.

The structure reflects a worldview.

This has implications for the AI systems we’re all building. When we create knowledge graphs for retrieval-augmented generation (and when we decide how to chunk content, what entities to extract, how to represent relationships) we’re doing philosophy whether we recognize it or not.

The ontology (or how the graph is built) shapes what the system can know and how it can know it.

But as an academic, I also understand the impulse to structure knowledge exists alongside the recognition that any structure is partial. A knowledge graph doesn’t capture knowledge. It creates a frame for retrieval. What lies outside the frame matters too.

There’s something almost mystical about this. The more carefully you map what you know, the more visible the boundaries of your knowing become. Structure reveals mystery rather than eliminating it.

The graph doesn’t contain the territory—it just makes certain paths through the territory easier to find.

This is where our own cultural and religious backgrounds, many of which are invisible, become key to understanding how we set up AI systems.

I don’t have this fully worked out. It’s one of the threads I want to pull on this year.

How do philosophical and contemplative traditions inform how we design these systems?

What would it mean to build a knowledge graph that acknowledges its own limits?

I’ve been wanting to explore this for a while now. Focusing my work even tighter around these topics and arguments give me the opportunity to go deeper in 2026.

What’s Ahead

For 2025, a few things:

I’ll continue the work on structured content, knowledge graphs, and testing systems—but now with the grant project providing a concrete laboratory. Students will be building something real. I’ll be writing about what we learn.

The Deep Reading podcast will keep going. Research that connects AI systems to rhetoric, history, and context. Short episodes, but substantive.

And I’ll be developing my course, Writing with Machines, which takes the prompt operations material I’ve been sharing and structures it into a learning path that helps writers and teams integrate AI in ways that enhance expertise without taking away agency.

Paid subscribers get access to the beta version of this course. I’ll be testing new material with them before it becomes a more polished offering through Firehead Digital Communications. If you want to dig into the structured prompting work and help me think through what’s useful, that’s the way in. More to come on this soon.

The university doesn’t provide resources for this kind of public scholarship. No course releases, no dedicated funding. Paid subscriptions help me continue the work—and I’m genuinely grateful for every one of them.

One last thought.

Building this knowledge graph was supposed to be an organizational project. It turned into something more like an examination of what I actually believe about my own work. The modeling surfaced assumptions I hadn’t articulated, connections I hadn’t named, and limits I hadn’t acknowledged.

Maybe that’s what structured content does at its best. Not capturing knowledge, but creating conditions for reflection—for ourselves, and eventually for the systems we build alongside us.

Here’s to a year of structuring, and of honoring what escapes the structure.

Metadata as Practice

One thing I’m committing to this year: tagging my own posts with the structure I’ve been writing about. Not just talking about AI-ready content—making it.

Here’s the metadata for this post:

Concepts: Knowledge Graphs, AI-Ready Content

Framework: Memory, ontology

Tools: Claude, Neo4j MCP

Builds on: “Is Structured Prompting Dead?”, “Testing as Rhetorical Proof”

Claims I’m making:

The ontology encodes the epistemology (definitive)

Building a knowledge graph is a form of reflection (provisional)

Structure reveals mystery rather than eliminating it (speculative)

The confidence levels matter.

I’m certain about #1.

I believe #2 but want more evidence.

#3 is something I’m testing—it might not survive contact with further thinking.

Over time, these tags will let me (and eventually you) trace how ideas develop across posts. That’s the hope, anyway.

What do you think?

Really strong work here. The part about separating rhetorical frameworks from concepts as an interpretive layer is smrt because it makes visible what was tacit in the content structure. I've seen similar shifts when teams start graphing their documentation and realized their "organization" was actually just chronology in disguise. The confidence levels on claims are a subtle touch that most people skip over.

Absolutely brilliant article, Lance. I am very excited to see where you go with this. The ontology you describe around arguments can also inform the structure and semantics of content itself. What if the ontology wasn't an overlay on the content but the framework you start with to write the content? Of course this structure would inform how you write a claim so as to convey the confidence you have at the time, or write the evidence such that it easily chunks and can be reused between claims.